Don Norman on How to Move Up in a Company: Think Big!

- 563 shares

- 2 years ago

The secret of Don Norman’s success is that this cognitive science and usability engineering expert advocates speaking in everyday language, taking a systems point of view and living a long life. By striving to emulate these and adopting a generalist approach, designers may find they can enjoy and use similar influence.

“Design, to me, I found was a perfect field because I could use all the science I knew, all the engineering I knew, all of the stuff about people and about technology, but I could produce and build things that were used by millions and millions of people.”

— Don Norman, “Grand Old Man of User Experience”

Learn how to succeed as a modern designer.

Video copyright info

Jerome Bruner by Poughkeepsie Day School (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

https://www.flickr.com/photos/poughkeepsiedayschool/10277703145

Three Mile Island by Nuclear Regulatory Commission (CC BY 2.0)

https://www.flickr.com/photos/nrcgov/17674734289

TMI-2 Control Room in 1979 by Nuclear Regulatory Commission (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

https://www.flickr.com/photos/nrcgov/7447591424

Stevens, Stanley Smith by Mark D. Fairchild

Fairchild M.D. (2016) Stevens, Stanley Smith. In: Luo M.R. (eds) Encyclopedia of Color Science and Technology. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-8071-7_314

This is a photograph of B.F. Skinner. by Msanders nti (CC-BY-SA-4.0)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:B.F._Skinner.jpg

EDSAC by Copyright Department of Computer Science and Technology, University of Cambridge. Reproduced by permission.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:EDSAC_(12).jpg

Two pieces of ENIAC currently on display in the Moore School of Engineering and Applied Science, in room 100 of the Moore building. Photo courtesy of the curator, released under GNU license along with 3 other images in an email to me.

Copyright 2005 Paul W Shaffer, University of Pennsylvania. by TexasDex (CC-BY-SA-3.0-migrated)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ENIAC_Penn1.jpg

Biblioteca de la UCSD by Belis@rio (CC BY-SA 2.0)

https://www.flickr.com/photos/belisario/2700271091/

This is an image of a place or building that is listed on the National Register of Historic Places in the United States of America. Its reference number is 78002444. by Bestbudbrian (CC-BY-SA-4.0)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:North_facade_of_College_Hall,_Penn_Campus.jpg

Atkinson Hall at the University of California, San Diego, housing the Qualcomm Institute—the UC San Diego division of the California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology (Calit2) by TritonsRising (CC-BY-SA-4.0)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Qualcomm_Institute.jpg

Don Norman became an influential figure for no small reason. A childhood fascination with electrons and electromagnetic waves led him to study electrical engineering at MIT. Slightly later, the University of Pennsylvania — where Norman was attending graduate school — was the home of some of the earliest computers. Norman wanted to get involved with computers, but settled on psychology. However, he wanted to study the mechanisms involved in psychology and began working at the Center for Cognitive Studies at Harvard. Here, renowned psychologist B.F. Skinner once denounced Norman’s work. This, Norman found, was a good thing; you need courage to do anything worthwhile — many people who follow established paths will dislike you for exploring beyond their frame of reference.

Norman then studied memory systems at Harvard (memory was a virtually-unknown study subject) before relocating to the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). Later, he and co-author Peter Lindsay wrote Human Information Processing: An Introduction to Psychology, a work examining how people process information — investigations that would sow the field of cognitive psychology. Considering psychology too narrow, Norman expanded into artificial intelligence, neural science, philosophy and other disciplines, and the UCSD’s Cognitive Science department was born.

In 1979, the Three Mile Island nuclear-power-station accident spotlighted the significance of Norman’s work and expansive knowledge base. Asked to investigate, Norman found the problem was the control room’s design. This incident drove him to design technology that improved what people experience. He began working on aviation safety for NASA, and strove to make computers easier to use (notably by working with Apple).

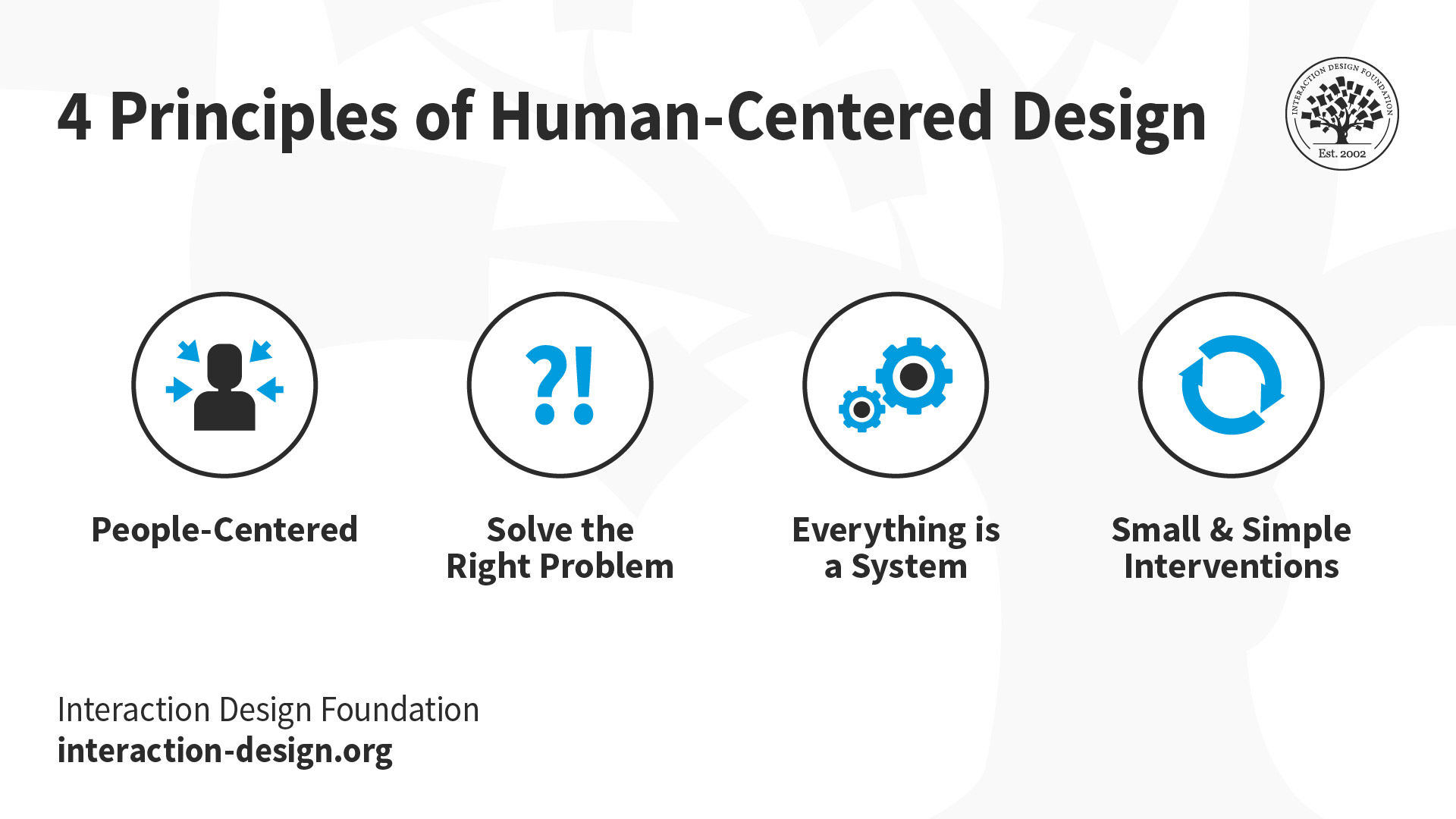

A year’s sabbatical at Cambridge University diverted Norman’s attention in an unexpected direction. Finding he couldn’t open some doors — their designs didn’t indicate to push or pull — Norman realized that principles governing nuclear safety and sophisticated devices also applied to basic artifacts. This inspired him to write The Psychology of Everyday Things. Later, he began the first of several retirements — at Apple, where he discovered some problems. Here, he coined the term “user experience,” became Apple’s user experience architect and began meeting designers in earnest. His influence has since extended to touch countless aspects of design. Still, Norman pressed on: encouraging designers to tackle the world’s biggest challenges with fundamental approaches such as 21st century design, human-centered design and humanity-centered design. His concern about the state of the world reflects his commitment to help designers realize they can make a difference if they apply human-centered design insights to the complex problems that plague our planet. And his work with the Interaction Design Foundation has resulted in a course — titled Design for the 21st Century — for designers to learn how they can achieve this.

© Daniel Skrok and Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 3.0

What can we learn from Norman’s experience? While Norman says he doesn’t really know what the secrets of his success are, he yields several points:

© Roman Kurachenko and Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 3.0

Everyday language makes life easy for the countless users, students and readers Norman has influenced. Academics traditionally write in complex, confusing ways.

The systems thinking viewpoint Norman takes to what he sees will help you decipher many complexities. That can also help you become influential, especially as you seek to rise in the organizations you help.

Old age is a privilege denied to many; it’s naturally difficult to “emulate.” Still, a powerful way to ensure “victory” over those who might stand in your way or attempt to mute your influence is to outlive them. Plus, providing the new areas and answers you explore are worthwhile ones, you can enjoy long-lasting effects of the positive outcomes you’ll have achieved.

Norman teaches a further key to success. Learn here how to leverage the power of being a generalist:

Apple's headquarters at Infinite Loop in Cupertino, California, USA. by Joe Ravi (CC-BY-SA-3.0) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AppleHeadquartersin_Cupertino.jpg Apple Museum (Prague) Apple II (1977). by Benoit Prieur (CC-BY-SA-4.0) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AppleMuseum(Prague)AppleII_(1977).jpg Apple Museum (Prague) Macintosh LC (1990). by Benoit Prieur (CC-BY-SA-4.0) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AppleMuseum(Prague)MacintoshLC(1990)(cropped).jpg Lucens, Versuchsatomkraftwerk by Josef Schmid (CC-BY-SA-4.0) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Controlroom-Lucensreactor-1968-L17-0251-0105.jpg Cali Mill Plaza, Cupertino City Center, at the intersection of De Anza and Stevens Creek Boulevards in Cupertino. by Coolcaesar (CC-BY-SA-3.0-migrated-with-disclaimers) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CupertinoCityCenter.jpg Atkinson Hall at the University of California, San Diego, housing the Qualcomm Institute—the UC San Diego division of the California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology (Calit2) by TritonsRising (CC-BY-SA-4.0) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Qualcomm_Institute.jpg Computer Museum: Xerox Alto Workstation by Carlo Nardone (CC BY-SA 2.0) https://www.flickr.com/photos/cmnit/2041103802 Xerox PARC in 1977; an un-busy weekend view from across Coyote Hill Road. Shot on an Olympus Pen-F, half-frame Kodachrome 64 slide; scanned by Pixel 3 phone with Moment 10X macro lens. by Dicklyon (CC-BY-SA-4.0) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:XeroxPARCin_1977.jpgVideo copyright info

Indeed, Don Norman had moved from one field to another to explore interests geared principally around human cognition — resulting in his ability to consider broader cause-and-effect chains of designers’ decisions. For example, with the nuclear power accident, he leveraged elements from engineering and psychology. Yes, Norman was self-taught; plus, his “timing” was remarkable. Nevertheless, you’ll find a powerful vantage point when you become a generalist:

You must know many different things, without sinking time into becoming expert at them. Instead, you consult many specialists, tap their in-depth expertise and bring them together to create a final product.

You can learn quickly. Everything you learn makes it easier to learn something else, and then the next new thing. You can then apply this snowballed knowledge to each new challenge.

You can decode complex situations more easily by viewing them from a generalist angle: a world of complex socio-technical systems, of interconnected parts of business, supply chains, technology and so much more.

Overall, remember; it takes courage to do things that will improve the world, one piece at a time.

Read Don Norman and Peter Lindsay’s ground-breaking work on Human Information Processing.

For a wealth of insights from Don Norman on the design of everyday things, check out his highly influential book.

Take our 21st Century Design course.

This post sheds further light on the benefits of generalists.

This Smashing Magazine piece examines an important aspect of Don Norman’s influence on design.

Here’s the entire UX literature on The Secret of Don Norman's Success by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into The Secret of Don Norman's Success with our course Design for the 21st Century with Don Norman .

In this course, taught by your instructor, Don Norman, you’ll learn how designers can improve the world, how you can apply human-centered design to solve complex global challenges, and what 21st century skills you’ll need to make a difference in the world. Each lesson will build upon another to expand your knowledge of human-centered design and provide you with practical skills to make a difference in the world.

“The challenge is to use the principles of human-centered design to produce positive results, products that enhance lives and add to our pleasure and enjoyment. The goal is to produce a great product, one that is successful, and that customers love. It can be done.”

— Don Norman

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!