This chapter is about hedonic or affective elements (footnote 1) of website design and the potential of such design to elicit emotion in the user. In an online environment hedonic elements of website design include color, images, shapes, and use of photographs, among other characteristics, which are expected to provide the user with emotional appeal, a sense of the aesthetic, or a positive impression resulting from the overall graphical look of a website (Cyr et al., 2009; Lavie and Tractinsky, 2003; Zhang, 2013). While it is well known that emotion is important to the interpretation of experience, it is only in recent years that research has begun to transcend utilitarian aspects of website design to consider empirically affective elements of design. Therefore, not only is it important that websites are useful and easy to use, but also that they entice the user to experience emotions such as enjoyment, involvement, trust, or satisfaction.

In this context, I focus on an empirically based research perspective that is anchored in the tradition of information systems (IS), and more specifically on the design of websites in the human computer interaction tradition (HCI). While much of the research considered is anchored in e-commerce, there are clearly implications for other types or applications such as e-government or social networking. In the following pages I therefore include the following: a brief retrospective examination of the development of a hedonic perspective in IS and design; an outline of some of the more commonly documented emotion-laden outcomes of website design; a consideration of graphical design elements known to elicit emotion in the user such as human images and color; an elaboration on the social elements of design; and a conclusion with a segment on future directions for research.

38.1 Emotion and Website Design: Some Background

38.1.1 Defining Emotion

According to Zhang, 2013 ( p. 247) “[A]ffect is conceived of as an umbrella term for a set of more specific concepts that includes emotion, moods, feelings...” Zhang continues (ibid, p. 251):

"One of the most complex affective concepts is emotion. Put simply, emotions are induced affective states (Clore and Schnall 2005), or core affect attributed to stimuli (Barrett et al. 2007; Russell 2003). Emotions typically arise as reactions to situational events in an individual’s environment that are appraised to be relevant to his/her needs, goals, or concerns. Once activated, emotions generate subjective feelings (such as anger or joy), generate motivational states with action tendencies, arouse the body with energy-mobilizing responses that prepare it for adapting to whatever situation one faces, and express the quality and intensity of emotionality outwardly and socially to others

(Damasio 2001; Izard 1993; Reeve 2005)"

Other researchers have identified a spectrum of feeling associated with emotion. For example, different emotions included by different authors have been anger, guilt, sadness, and fear/anxiety (Smith and Lazarus, 1993), or joy, fear, anger, sadness, disgust, shame, and guilt (Scherer, 1997). Emotion, therefore, has been seen to have both negative and positive valence (Cenfetelli, 2004; Roseman et al., 1996). Emotional responses are known to have two components: arousal and valence. Arousal reflects the intensity of the response, while valence refers to the direct emotional response ranging from positive to negative (Russell, 1980; Deng and Poole, 2010).

With website design, it is expected that emotion is aroused in the user based on a response to specific design elements. Therefore, the user may feel a sense of satisfaction when website colors are appealing, or when a graphical design elicits enjoyment or excitement. In addition, it is important that website design meets the needs and sensibilities of the user. This may include website design that is particular to subgroups with specific preferences. The author’s research has identified that there are different website design preferences for men and women, or for users in different national locations. These differences will be elaborated in the following pages. If website design is appropriate to the user, then this arouses the action tendencies described by (Zhang (2013); above, including users being more loyal to the site, and returning there in the future.

38.1.2 Beyond Cognitive-based Paradigms

Despite the pervasiveness of emotional reaction in the human psyche, only within the last decade have calls been made for a break with conventional cognition-driven paradigms of studying user reactions to technology (Beaudry and Pinsonneault, 2010; Zhang and Li, 2004). In their place is an expanded focus that includes not only utilitarian outcomes such as usefulness or ease of use, but also the role of affect and emotion in the examination of information and communication technology systems (Kim et al., 2007; Sun and Zhang, 2006). For instance, Hassenzahl 2006 (p. 266) elaborates:

"In HCI, it is widely accepted that usability is the appropriate definition of quality. However, the focus of usability on work-related issues (e.g., effectiveness, efficiency) and cognitive information processing has been criticized. Its quite narrow definition of quality neglects additional hedonic (non-instrumental) human needs and related phenomena, such as emotion, affect and experience"

Further, Zhang (2013) outlines:

Affect is a critical factor in human decisions and behaviors within many social contexts. In the information and communication technology context (ICT), a growing number of studies consider the affective dimension of human interaction with ICTs. However, few of these studies take systematic approaches, resulting in inconsistent conclusions and contradictory advice for researchers and practitioners.

To date, some research has been conducted in the area of emotion when users are in online environments. For instance, hedonic outcomes have been examined in terms of flow (Eroglu et al., 2003; Griffith et al., 2001; Ha et al., 2007; Huang, 2006; Koufaris et al., 2002); cognitive absorption (Agarwal and Karahanna, 2000; Wakefield and Whitten, 2006), involvement (Fortin and Dholakia, 2003; Johnson et al., 2006), playfulness (Wakefield and Whitten, 2006), enjoyment (Dickinger et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2000; Li et al., 2008; Lin and Bhattarcherjee, 2008;2010; Sun, 2001; Sun and Zhang, 2006; van der Heijden, 2004; Venkatesh, 2000; Wakefield and Whitten, 2006), hedonic outcomes (Venkatesh and Brown, 2001), pleasure (Belanger et al., 2002), happiness (Beadry and Pinsonneault 2010), fun (Dabholkar, 1994; Dabholkar and Bagozzi, 2002), stimulation (Fiore et al., 2005), or mystery (Rosen and Purinton, 2004), among others.

Further, various studies are emerging that examine emotion more specifically related to design elements, including design of e-commerce websites. This is important since Lam and Lin (2004) argue that the role of emotions in online shopping is even more important than in traditional marketing contexts because the consumer is disengaged from human interaction. To this end, user emotional responses have been measured with respect to “design factors” such as shapes, textures, color (Kim et al., 2003), visual characteristics of web pages (Lindgaard et al., 2006), or web page aesthetics (Robins and Holmes, 2008). Additional topics covered are affective user interfaces (Johnson and Wiles, 2003; Lisetti and Nasoz, 2002); hedonic quality (Childers et al., 2001; Hassenzahl, 2002; van der Heijden 2003, 2004); aesthetic performance including atmospheric cues, media richness and social presence (Lim and Cyr, 2009); presentation richness such as symbol variety (Jahng et al., 2002); interaction richness (Jahng et al., 2007); human images (Cyr et al., 2009); color (Cyr et al., 2010); or vividness (Jiang and Benbasat, 2007). Cyr et al. (2006) found that design aesthetics on a mobile device resulted in enjoyment, and ultimately online loyalty. Similarly, Sony Ericsson’s website for Egypt (Figure 1) is aimed to promote variety and fun (Seidenspinner and Theuner, 2007).

Author/Copyright holder: Sony Ericsson. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine (as permission could not be obtained). See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "allRightsReserved-UsedWithoutPermission") on the page copyright notice.

Figure 38.1: Sony Ericsson Egypt: Promoting Variety and Fun (in Seidenspinner and Theuner, 2007).

A note on the use of illustrations in this chapter: In many cases these figures are reproduced from the original article where they appeared. These figures are used for general illustrative purposes only, and it is not intended that full readability is required

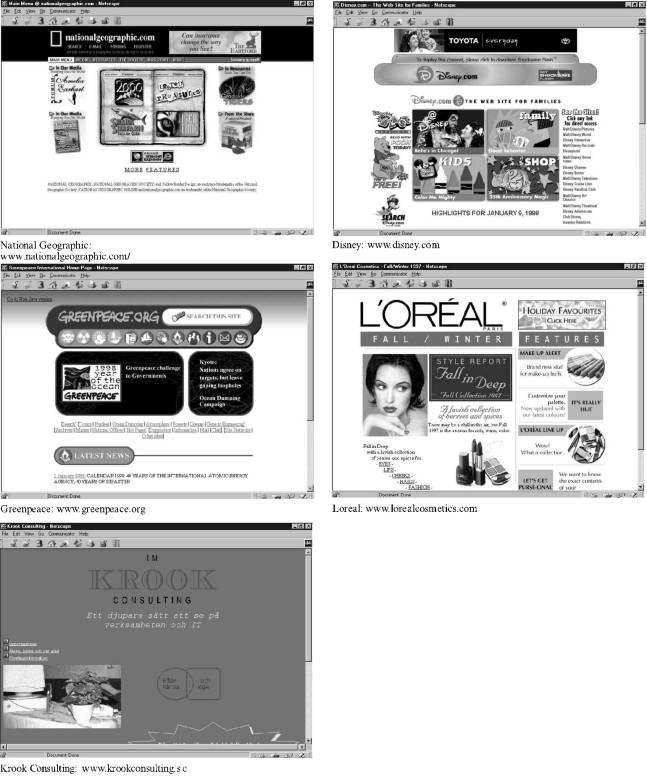

Over the years, beauty has been a precursor to emotional responses. In website design various researchers have focused on aesthetic beauty (footnote 2) (e.g. Karvonen, 2000; Lavie and Tractinsky, 2004). Schenkman and Jonsson (2000)examined beauty on a sample of web pages (Figure 2) using multi-dimensional analysis. They found four categories that viewers used to judge a web page: beauty; illustrations versus text; overview (i.e. lucid, clear, and easy to understand); and structure. Overall, the researchers found the best predictor of overall judgment of the website was beauty. Based on user judgments, these websites were scored for perceived beauty out of a maximum of seven: National Geographic (5.08), Disney (4.51), Greenpeace (3.93), L’Oreal (5.55), and Krook Consulting (2.70).

Author/Copyright holder: Courtesy of National Geographic, Disney, Greenpeace, L'Oreal Cosmetics, and Krook Consulting. Copyright terms and licence: compositeWorkWithMultipleCopyrightTerms (Work that is derived from or composed of multiple works with varying copyright terms and/or copyright holders).

Figure 38.2: Sample Web Pages related to Beauty.(in Schenkman and Jonsson, 2000)

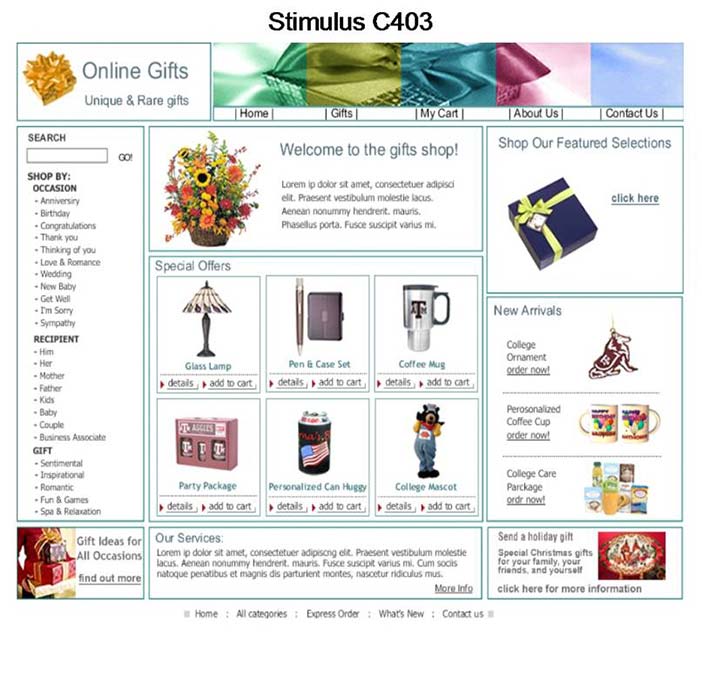

Deng and Poole (2010) examined web page visual complexity and order and found a relationship to user emotions and behavior. Website complexity was dependent on the number of links, graphics, and the amount of text that appear on the web page. Figure 3 shows examples of low website complexity (12 links/2 graphics/33 text) versus high website complexity shown in Figure 4 (54 links/14 graphics/118 text).

Author/Copyright holder: Unknown Website (manipulated/synthesized in Deng and Poole, 2010). Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine (as permission could not be obtained). See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "allRightsReserved-UsedWithoutPermission") on the page copyright notice.

Figure 38.3: Sample of a Web Page Low in Visual Complexity (in Deng and Poole, 2010)

Author/Copyright holder: Unknown Website (manipulated/synthesized in Deng and Poole, 2010). Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine (as permission could not be obtained). See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "allRightsReserved-UsedWithoutPermission") on the page copyright notice.

Figure 38.4: Sample of a Web Pages High in Visual Complexity (in Deng and Poole, 2010)

Order refers to the logical organization, coherence, and clarity of the web page content. An additional component of the research is the degree to which the meta-motivational state of the user (e.g. extent to which a user seeks stimulation from the site) influences the user’s impression of the website. It was found that whether a user was more focused or more relaxed in approach when viewing a website did have an effect on whether the website was perceived as pleasant. This second finding suggests that not only is the actual design of the website important to eliciting an emotional reaction from the user, but also that the user’s motivational state will have some bearing on how the website is viewed and evaluated.

Scholars have also examined how social elements such as pictures of people or emotive text on websites empirically impact users’ impressions such as enjoyment (Cyr et al. 2006; Gefen and Staub 2003; Hassanein and Head, 2007). (footnote 3) Many of these studies, particularly in the e-commerce realm, have user outcomes of trust (Bhattacherjee, 2002; Chen and Dhillon, 2003; Cheung and Lee, 2006; Cyr, 2008; Everard and Galletta, 2006; Gefen et al., 2003; Jarvenpaa et al., 2000;Komiak and Benbasat, 2004 ; Koufaris and Hampton-Sosa, 2004; Wang and Benbasat, 2005) and satisfaction (Agarwal and Venkatesh, 2002; Fogg et al., 2002; Hoffman and Novak, 1996; Koufaris, 2002; Lindgaard and Dudek, 2003; Nielsen, 2001; Palmer, 2002; Szymanski and Hise, 2000; Yoon, 2002).

Further research has aimed to develop models that incorporate hedonic elements. Related to affect, Loiacono and Djamasbi (2010) proposed the relevance of mood (such as sadness, fear, or happiness) for system usage models that could be applied online. They further outlined a model in which mood is intended to influence perception, evaluation, and cognitive effort resulting in variable levels of IS usage behavior. While this model is not tested, it is a useful framework from which to investigate emotion empirically.

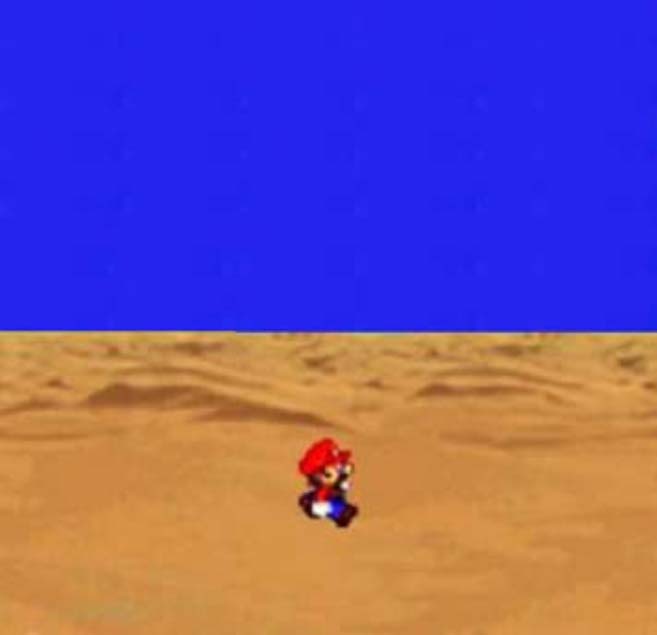

In addition, Lowry et al. (forthcoming 2013) developed a hedonic system adoption model focused on a user’s intrinsic motivations. Using an immersive gaming environment, various games were rigorously tested to determine perceived levels of joy and ease of use. A game that scored “low” on both dimensions was a text-based adventure game with minimal graphical content (Figure 5).

Author/Copyright holder: Nintendo Co., Ltd. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine (as permission could not be obtained). See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "allRightsReserved-UsedWithoutPermission") on the pagecopyright notice.

Figure 38.5: Gaming Environment Low in Hedonic Value (from Lowry et al., 2013)

In contrast, the game scored by users as “high” for joy and ease of use was highly interactive, with complex colors and graphics (Figure 6). Using various game interfaces, these researchers determined that perceived ease of use resulting in behavioral intention to use, or the user’s experience of immersion, is mediated by hedonic constructs such as curiosity or joy (along with perceived usefulness and control). Hence the role of affectively based constructs is central to understanding the user experience in a variety of web-based platforms, including gaming.

Author/Copyright holder: Heroes of Might and Magic V. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine (as permission could not be obtained). See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "allRightsReserved-UsedWithoutPermission") on the page copyright notice.

Figure 38.6: Gaming Environment High in Hedonic Value (from Lowry et al., 2013)

38.1.3 Summary

It is encouraging that over the past decade, researchers have expanded beyond utilitarian models of online experience to encompass how users are also emotionally engaged. While substantial progress has been made in this area, only recently have researchers created comprehensive models to evaluate how hedonic systems operate. Hence, there is considerable scope for future work that empirically explores variables that elicit hedonic or affective responses in the user, with a goal of theory development in this domain. The spectrum for such research is broad, and encompasses e-commerce, gaming, e-health, and many additional contexts.

In general, emotional responses are triggered by an ability to engage the user in an online environment which is aesthetically pleasing. This places the elicitation of emotion firmly in the realms of visual design and interaction design. However, there is no clear definition as to what represents a hedonic outcome—and, based on the literature to date, these outcomes have varied widely. As such, there is scope for studies that add clarity and consistency to how hedonic systems impact the user. In an effort to consolidate the literature to date, in the following sections I have chosen to discuss four hedonic outcomes: enjoyment, involvement, trust, and satisfaction. These have particular importance in an e-commerce setting, but are relevant in online contexts more generally. These constructs have received considerable use and have been validated in numerous studies.

38.2 Outcome Variables that Elicit Emotion

38.2.1 Enjoyment

As early as 2003, Blythe and Wright (2003) (p. xvi) argued that in HCI “traditional usability approaches are too limited and must be extended to encompass enjoyment”. Perhaps more than any other construct, enjoyment has been used to measure user hedonic perceptions and expectations on websites (e.g. Dellaert and Dabholkar, 2009; Gretzel and Fersnemaier, 2006;Hassanein and Head, 2005 ; Koufaris et al., 2001; Koufaris, 2002; Lee et al., 2000; Li et al., 2008; Sun, 2001; Sun and Zhang, 2006;Qui and Benbasat, 2009 ; Venkatesh, 2000). Other work (e.g. Warner, 1980 (footnote 4)) has suggested enjoyment encompasses three dimensions: engagement, positive affect, and fulfillment. Enjoyment has also been subsumed under the concept of flow (as originally identified by Csikszentmihalyi, 1989 (footnote 5)). Although Dabholkar (1994) and Dabholkar and Bagozzi (2002) employed the term “play” in place of enjoyment in their research, they admitted that the meaning of “play” is no different from that of enjoyment. (footnote 6)

Although enjoyment is a commonly used construct to measure user reactions to hedonic content on the web, it is surprising that the accurate measurement of enjoyment has tended to be elusive. For example, as recently as 2008, Lin et al. 2008(p. 41) noted: “[W]hen we came to the question of assessing the degree to which enjoyment arises from a Web encounter, we found remarkably little to guide us...and no instrument for assessing enjoyment of Web experiences could be found.” To this end, they created and validated an instrument for online enjoyment with three dimensions: engagement, positive affect, and fulfilment, as suggested earlier by Warner (1980). This instrument is a positive step forward to create ways in which to accurately measure user responses, and thus inform web managers and markets as to what constitutes meaningful and enjoyable website design.

Further, the concept of enjoyment has been revealed to be “a strong predictor of attitude in the web-shopping context” (Childers et al., 2001, p. 526; Cyr et al., 2006, 2007; Hassanein and Head, 2006; Lankton and Wilson, 2007; Koufaris et al., 2002; van der Heijden, 2003; Zhang and von Dran, 2002). In online settings, a primary goal of vendors is to entice users to purchase from websites or to revisit them in the future, resulting in loyal behavior (Rosen and Purinton, 2004). Online loyalty (or e-loyalty) has been described as an enduring psychological attachment by a customer to a particular online vendor or service provider (Anderson and Srinivasan, 2003; Butcher et al., 2001). Jiang and Benbasat (2007) discovered that vividness and interaction of consumer product displays for a watch and Personal Data Assistant (PDA) resulted in enjoyment and e-loyalty.

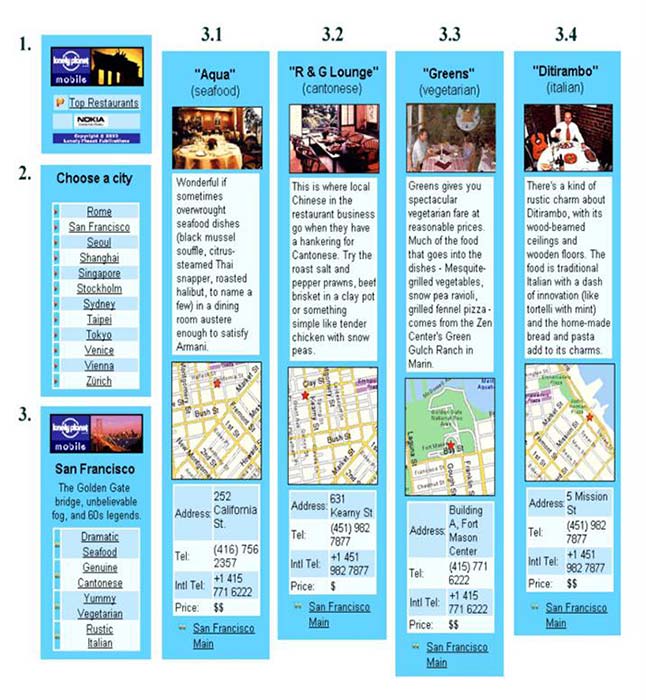

In a study of mobile interfaces as used in an e-service shopping environment, researchers found the “design aesthetics” of the interface positively impacted enjoyment, usefulness, and ease of use, which in turn positively affected user loyalty (Cyr et al., 2006). More specifically, Design Aesthetics referred to the following: attractiveness of the screen design (e.g. colors, boxes, menus); professional design; meaningful graphics; and overall “look and feel” as visually appealing (Figure 7).

Author/Copyright holder: LonelyPlanet Inc. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine (as permission could not be obtained). See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "allRightsReserved-UsedWithoutPermission") on the page copyright notice.

Figure 38.7: Screen Shots used to Test Design Aesthetics (in Cyr et al., 2009)

38.2.2 Involvement

For many years involvement has been the object of considerable consumer-oriented research. Although there have been numerous definitions of involvement, Koufaris 2002(p. 211) summarized involvement as: “(a) a person’s motivational state (i.e. arousal, interest, drive) towards an object where (b) that motivational state is activated by the relevance or importance of the object in question...” If the website permits involvement for the user, then it will result in an affective response that will be greater than an elicited cognitive reaction (Fortin and Dholakia, 2003). Online, involvement implies a user emotional response that includes absorption and excitement with website characteristics (e.g. Kumar and Benbasat, 2002; Santosa et al., 2005; Singh et al., 2003), and therefore encompasses elements of “flow”. Jiang et al. (2010) refer to “affective involvement” as a heightened emotional feeling associated with a website comprising how users feel toward the website.

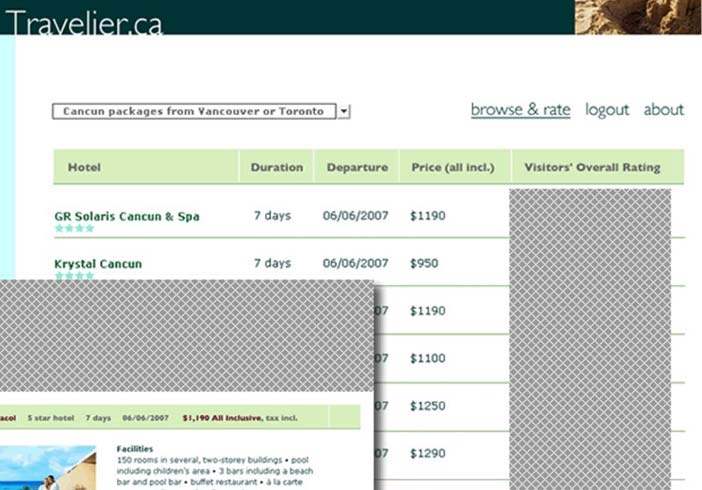

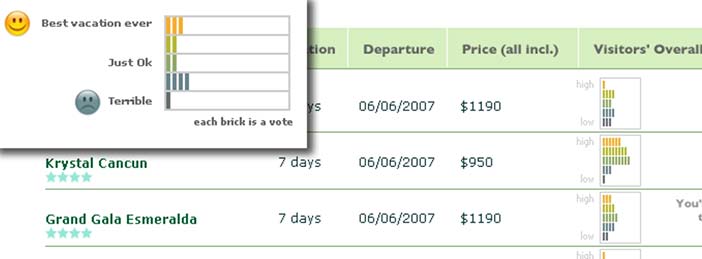

In terms of website antecedents that result in involvement, website interactivity has played a prominent role (Fortin and Dholakia, 2003; Johnson et al., 2006). (footnote 7) Interactivity potentially enables the user to have augmented control of the content, and thus offers an opportunity for the user to interact with the advertiser and/or other consumers (Fortin and Dholakia, 2003). Involvement was found to have a “pivotal role” (ibid, p. 394) in understanding how consumers interact with websites, and thus influences consumer loyalty toward the site. In research that examined different levels of interactivity in a fictitious vacation website (Cyr et al., 2009), five different web-poll designs (footnote 8) (Figure 8) were tested with users. The designs range from no user interaction in Treatment 1 to high interactivity and visualization capability in Treatments 4 and 5.

Based on survey results, perceived website interactivity resulted in user perceptions of efficiency, effectiveness, enjoyment and trust, and ultimately online loyalty (Cyr et al., 2009). Although there were no statistically different results for the different web-poll treatments in Figure 8, additional qualitative analysis revealed that users had more positive impressions of the more interactive websites. Relevant to the topic of emotion and website design, different concepts emerged, which included “Affective” and “Aesthetic” categories. For instance, for Aesthetics users noted the websites were “visually appealing”, “unique”, “creative”, “stylish and innovative”. For the Affective category, users described the sites as “exciting”, “makes the customers feel more empowered by allowing them to influence others using the poll system”, “has a warm feeling to it”, is “entertaining” and “fun”.

Author/Copyright holder: Dianne Cyr. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

The content above was common to all treatments. There were three pages in total: the front page with a list of hotels and a summary, and two detail pages. These two (one shown as the smaller cutout) included photos, description and the actual web-poll at the top. The gray-striped area is where design varied.

Author/Copyright holder: Dianne Cyr. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Treatment 1: Control version. No user interaction with web-poll; static indicator of other users’ rating only.

Author/Copyright holder: Dianne Cyr. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Treatment 2: Basic web-poll with conventional interaction (radio button) and simple information visualization (bar chart)

Author/Copyright holder: Dianne Cyr. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Treatment 3: Metaphor-rich web-poll. Cursor reveals foot icon across sandbox to select one of nine possible value combinations on a grid. Mini plot on front page with size of dot displaying number of votes.

Author/Copyright holder: Dianne Cyr. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Treatment 4: Flash version for enhanced user control. Cursor changes into foot icon, moving on scale continuously. Front page summary uses color lightness to represent weight. Bar levels give a positive/negative ‘slope’ for before and after.

Author/Copyright holder: Dianne Cyr. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Treatment 5: Enhanced Bar Chart version for visualizing user contribution. Users ‘viscerally’ plot their vote to the stack by adding a ‘brick’

Figure 38.8: Five Levels of Website Interactivity (in Cyr et al., 2009)

38.2.3 Trust

Website usability can significantly impact trust (Flavián et al., 2006). In online environments numerous researchers have endeavored to understand the complexities inherent in trust (Bhattacherjee, 2002; Chen and Dhillon, 2003; Cheung and Lee, 2006; Gefen, 2000; Gefen et al, 2003;Jarvenpaa et al., 2000 ; Komiak and Benbasat, 2004; Koufaris and Hampton-Sosa, 2004;Rattanawicha and Esichaikul, 2005 ; Wang and Benbasat, 2005; Yoon, 2002). (footnote 9) Online trust relates to consumer confidence in a website and willingness to rely on the vendor in conditions where the consumer may be vulnerable to the seller (Jarvenpaa et al., 1999). Trust has an emotional component, and according to Komiak and Benbasat (Komiak and Benbasat 2006, p. 943) “[E]motional trust is defined as the extent to which one feels secure and comfortable about relying on the trustee”. Unlike the vendor-shopper relationship established in traditional retail settings when trust is assessed in a direct and personal encounter, the primary communication interface with the vendor is an information technology artifact, the website. An absence of trust is one of the most frequently cited reasons that consumers refrain from purchasing from Internet vendors (Grabner-Kräuter and Kaluscha, 2003).

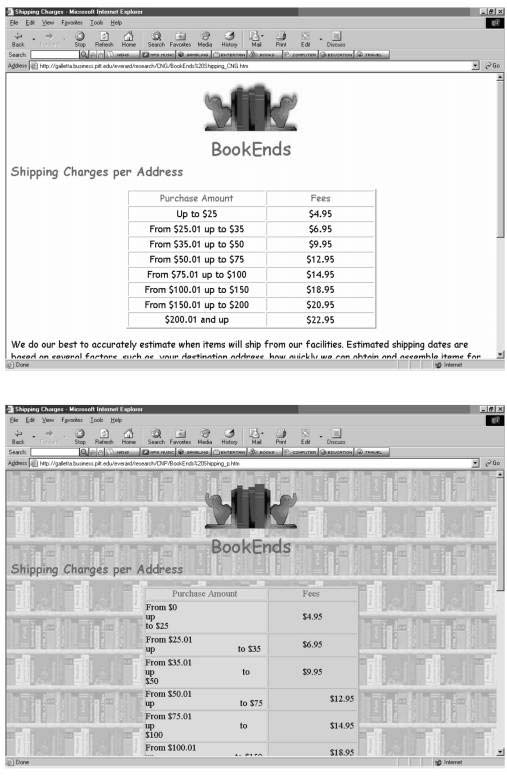

Various studies have shown that website trust is fundamental to e-loyalty including online purchase intentions (Flavián et al., 2006; Gefen, 2000; McKnight et al, 2004), and willingness by consumers to buy from an online vendor (Flavián et al., 2006; Laurn and Lin, 2003; Pavlou, 2003). Antecedents to user trust in websites vary, and include website design characteristics (Flavián et al., 2006) and design credibility (Green and Pearson, 2011). Everard and Galletta (2005-6) conducted a study in which they examined how presentation flaws on websites (e.g. errors, poor style, incompleteness) influence user perceptions. More specifically, websites were experimentally created to demonstrate good versus poor quality (Figure 9). Results of the investigation found that user perceptions of flaws on the website related to perceived quality—which was in turn directly related to trust and intention to purchase from the store. Thus, careful attention to detail and the elimination of design flaws has a positive impact on the user.

Author/Copyright holder: Everard and Galletta (2005). Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in thecopyright terms below.

Figure 38.9: Samples of Web Pages for Good (upper) versus Poor Style (in Everard and Galletta (2005-6)

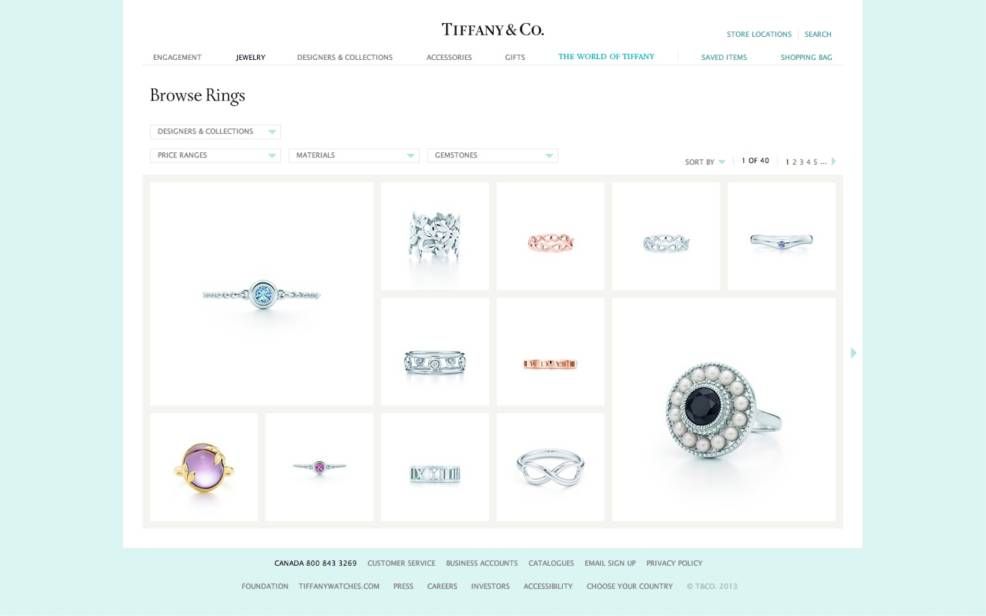

A relationship exists between beauty of a website and trust (Karvonen, 2000). More specifically, images have the power to enhance consumer trust in a vendor. In this vein, jewelry retailer Tiffany and Co. invested in digital imaging technology to ensure images of jewelry are presented on its website in such a way as to instill trust in potential buyers (Srinivasan et al., 2002). Refer to Figure 10.

Author/Copyright holder: Tiffany and Co. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine (as permission could not be obtained). See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "allRightsReserved-UsedWithoutPermission") on the page copyright notice.

Figure 38.10: A Sample Web page from Tiffany and Co.

Additional triggers of online trust include vendor size (van der Heijden et al., 2000), perceived vendor reputation (Jarvenpaa et al., 2000; Koufaris and Hampton-Sosa, 2004;Van der Heijden et al., 2000), service quality (Gefen, 2002), social presence (Gefen and Straub, 2003), and perceived security control (Koufaris and Hampton-Sosa, 2004).

38.2.4 Satisfaction

Satisfaction on the web relates to "stickiness" and the sum of all the website qualities that induce visitors to remain at the website rather than move to another site (Hoffman and Novak, 1996). An effectively designed website engages and attracts online consumers, resulting in online satisfaction (Agarwal and Venkatesh, 2002; Fogg et al., 2002; Hoffman and Novak, 1996; Koufaris, 2002; Lindgaard and Dudek, 2003;Nielsen, 2001 ; Palmer, 2002; Szymanski and Hise, 2000; Yoon, 2002).

Elements of website design that contribute to satisfaction are numerous and varied. Palmer (2002) validated design metrics for websites and found that site organization, information content, and navigation are important to website success—including user intent to return to the site. In other research, website design and the "ambience associated with the site itself and how it functions" is an antecedent to satisfaction (Straub, 1989). In alignment with other researchers (e.g. Agarwal and Venkatesh, 2002; Cronbach, 1971; Falk and Miller, 1992), website satisfaction is defined here as overall contentment with the online experience. Website satisfaction is frequently a predictor of e-loyalty (Flavián et al, 2006; Kim and Benbasat, 2006; Lam et al., 2004; Laurn and Lin 2003; Yoon, 2002).

38.2.5 Summary

From the preceding, it is clear that if websites are effective and are able to arouse responses in users such as enjoyment, involvement, trust, or satisfaction, then they will be successful in enticing users to return to the site. These findings are intuitive, but in the present article they are also founded on considerable systematic and rigorous investigation by researchers—mostly in the information systems area. However, beyond pure research, these results have merit for practitioners such as web strategists and designers. As a powerful communication mechanism for commercial or other use, effective website design has the ability to persuade. Hence, a worthy goal is the amalgamation of work from both the academic research and design communities to forge new and deeper understandings as to how emotion and websites are tied together. This calls for integrated and multidisciplinary approaches—as well as multiple methods for assessing user reactions to website design elements.

38.3 Graphical Website Design Elements: A Focus on Color and Images

Although a number of website elements could be considered in depth concerning their ability to impact the user, this chapter focuses on the website characteristics of color and imagery. These two elements are not only central in website design, but they also have interesting cultural implications for the user that merit future consideration. Thus we begin with an overview of color and website design—including how color preferences vary by country. This is followed by an overview of images, similarly with some discussion as to how imagery is perceived by users from different countries.

38.3.1 Color and Emotion

The study of color and color appeal has interdisciplinary connections. Color has been studied by a variety of researchers—from artists to zoologists—including the use of color in art (Fornell, 1982) or visual perception (Gorn et al., 1997). Psychologists have been interested in the effect of color on individual preferences (Goldberg et al., 2002). Some colors are able to arouse and excite an individual, while other colors elicit relaxation. Research on color suggests hue (as in primary colors red, blue, yellow), brightness (light colors such as white versus dark colors such as black or gray), and saturation (intense versions of a color versus pastels) all have an effect on individual reactions and perceptions (Latomia and Happ, 1987).

"Colors are known to possess emotional and psychological properties" (Lichtle, 2007, p. 91), and have the potential to convey commercial meaning in products, services, packaging, and Internet design. For many years, marketers have utilized the power of color for logos or displays to build consumer confidence in the corporate brand (Lui et al., 2004; Rivard and Huff, 1988). Cool colors such as blue and green are generally viewed more favorably than warm colors such as yellow or red (Goldberg and Kotval, 1999; Latomia and Happ, 1987; Marcus and Gould, 2000). Blue is generally associated with "wealth, trust, and security" (Lichtle, 2007) and is universally liked (Carte and Russell, 2003; Meyers-Levy and Peracchio, 1995; Nielsen and Del Galdo, 1996). In part, this explains the use of blue by corporate entities such as banks (at least in North America) or IBM to establish a professional and credible image. Red is the color symbolizing Coca Cola. Alternately, orange denotes "cheapness" (Lichtle, 2007).

Although color has the potential to elicit emotions or behaviors, in only a handful of studies are various website color treatments empirically tested regarding their impact on user trust or satisfaction. However, Cyr (2008) found that visual design of the website (which includes color) resulted in trust, satisfaction, and loyalty. Further, Kim and Moon (1998) examined color and four other design factors on an online banking interface. Color elements examined were color tone (e.g. warm or cool), main color (e.g. primary or pastel), background color, brightness, and symmetry (how color was organized). The findings show that color has a main effect on trustworthiness of the interface. Color likewise has an influence on behavioral intentions such as customer loyalty, with blue producing stronger buying intentions than red (Becker, 2002; Latomia and Happ, 1987).

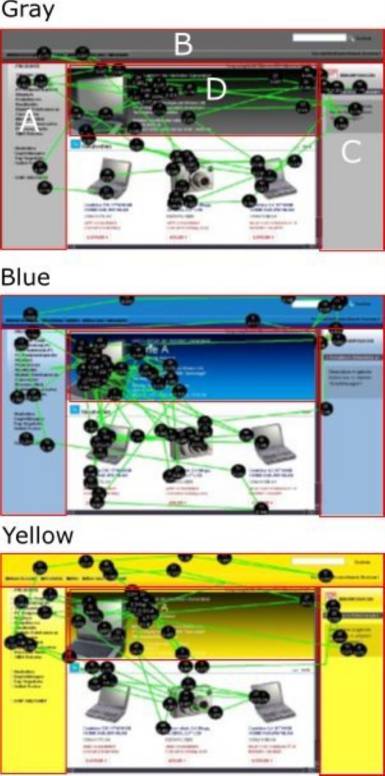

In a study aimed to investigate the impact of color related to user emotion and perceptions of website appeal, Bonnardel et al. (2011) tested a variety of colors to determine whether the user found the site to be pleasing, appealing, and appropriate (Figure 11). By varying hue and intensity 23 pages were created. (footnote 10) Testing with groups of participants with varied backgrounds, including web designers, yielded consistent color effects—with blue as the most preferred color, and gray as the least preferred. Additionally, color impacted how users navigated the site and the information they retained.

Author/Copyright holder: Bonnardel et al., 2011. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Figure 38.11: Samples of Diverse Color Use on Websites (in Bonnardel at al., 2011)

38.3.2 Culture and Color

Two opposing views exist when culture, color, and cognition intersect. A Universalistic view prescribes generic cognitive processing of color perception. Alternately, Cultural Relativism suggests that color perception is mostly shaped by culturally specific language associations and perceptual learning (Berlin and Kay, 1969; Kay et al., 1991). For the Internet, the prevailing view is more aligned to Cultural Relativism in that ideally websites should be developed for specific cultural and user groups—termed website localization (Barber and Badre, 1998; Cyr and Trevor-Smith, 2004). When localizing a website, in addition to language translation, details such as currency, color sensitivities, product or service names, images, gender roles, and geographic examples are considered (footnote 11). Localized website design creates alignment to user expectations, and according to an ISO quality standard this is a critical success factor for effective and efficient task completion.

Color connotes different meaning in different cultures (Bagozzi and Yi, 1989; Barber and Badre, 1998; Singh et al., 2003). Red means happiness in China, but danger in the United States. In a cross-cultural study focused on understanding the meaning and preferences for ten colors across eight countries, blue was generally considered "peaceful" or "calming" (Madden et al., 2000). In contrast, brown and black had associations of "sad" and "stale" across cultures. Other colors, such as yellow and orange, showed less cross-cultural consistency in terms of how they were perceived.

In the information systems and e-commerce realm, a growing number of studies have been published with respect to culture and website design, and the subsequent effect on users. In a report in which 27 research studies published in 16 different journals were evaluated for website cultural congruency (e.g. cultural adaption), strong empirical support was provided for the positive impact of cultural congruency on performance measures including website effectiveness (Vyncke and Brengman, 2010). (footnote 12) Other investigations support unique user preferences for website design characteristics in different countries and cultures. For instance, for a study in which domestic and Chinese websites for 40 American-based companies were systematically compared, significant cultural differences were uncovered for all major categories tested (Singh et al., 2003). (footnote 13)

Especially rare are rigorous studies which are primarily focused on color in website design across cultures. This area represents an important and overlooked topic. According to Noiwan and Norcio (Noiwan and Norcio 2006, pp. 103, 104), “[E]mpirical investigations on the impacts of cultural factors on interface design are absolutely vital... Interface designers need to understand color appreciation and color responses of people in different cultures and regions."

In a study comparing Indian and U.S. websites related to language, pictures, symbols, and colors substantial differences were found regarding the use of color (Kulkarni et al., 2012). The Indian portal (Figure 12) had multiple colors on a white background, while the U.S. website (Figure 13) hosted only blue and red, which, as the authors point out, are represented on the national flag.

Author/Copyright holder: Bharat.gov.in. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine (as permission could not be obtained). See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "allRightsReserved-UsedWithoutPermission") on the page copyright notice.

Figure 38.12: An Indian Portal (in Kulkarni et al., 2012)

Author/Copyright holder: Courtesy of USA.gov. Copyright terms and licence: pd (Public Domain (information that is common property and contains no original authorship)).

Figure 38.13: A U.S. Portal (in Kulkarni et al., 2012)

From this study it appears that the use of specific colors on websites in different countries can also impact color appeal, trust and satisfaction.

Cyr and Trevor-Smith (2004) examined design elements, including the use of color, using 30 municipal websites in each of Germany, Japan, and the U.S (90 websites in total). Use of symbols and graphics, color preferences, site features (links, maps, search functions, page layout), language and content were examined, and significant differences were determined in each website design category. Colors used on a website were matched to a color wheel and assigned a numerical value by independent raters based on the percentage of the page on which a color appears. (footnote 14) Fifteen colors were used across the websites. Relevant to the countries in this investigation, blue was most popular on German websites, while gray was the color most often appearing on American websites. Japanese are known to prefer brighter colors such as yellow (also supported by Noiwan and Norcio, 2006).

Building on empirical results from the few studies in which color is examined on websites, Cyr et al. (2010) examined the influence of blue, gray, and yellow on color appeal, trust, satisfaction, and online loyalty. Figure 14 illustrates a sample of how color is adapted. (footnote 15) Testing was conducted on 30 participants from each of Canada, Germany, and Japan (90 total). These countries were chosen based on known cultural diversity (e.g. Hofstsede, 1980). Data was collected using a questionnaire, interviews, and an eye-tracker. (footnote 16) Website color appeal was found to be a significant determinant of website trust and satisfaction, with differences across cultures. More specifically, Canadians, Germans, and Japanese all tend to dislike yellow on websites. Users in all three countries most prefer the blue sites, contrary to expectations that Japanese would prefer a bright color.

Of particular relevance to a discussion of emotion and websites, from interview analyses five concepts emerged from the data related to use of color on the website: (1) aesthetics concerning artistic appeal, (2) affective or emotional quality of the color, (3) functional quality, (4) harmony (i.e. balance), and (5) appropriateness (Cyr et al., 2010). As already noted, color has the ability to elicit an emotional or affective response toward a website, and this varied across the various groups. For instance, in all three countries blue had positive affective quality while in none of the countries did users mention this was the case for gray.

Author/Copyright holder: Cyr et al., 2010. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Figure 38.14: Sample Websites indicating Color Zone Treatments and Look Zones for a German Website (preliminary experimental treatments adapted from Cyr et al., 2010)

38.3.3 Imagery and Emotion

Image design for websites may include elements of balance, emotional appeal, aesthetics, and uniformity of the overall graphical look of the site. This encompasses web elements such as use of photographs, colors, shapes, or font type (Garrett, 2003). The aesthetics of website design are considered related to the “overall enjoyable user experience” (Tarasewich, 2003, p. 12). The use of photographs in websites has been debated among usability experts in a discussion of whether photographs unnecessarily clutter up the website, slow it down, and disrupt its functionality (Riegelsberger, 2002). Alternately, images have been found to attract viewer attention (Riegelsberger, 2002), and increase credibility (Fogg et al., 2002).

In advertising, images are used to convey product and brand information—and to elicit emotional responses from consumers (Branthwaite, 2002; Kamp and MacInnis, 1995; Swinyard, 1993). In one study, a picture of a spray bottle of window cleaner composed of purple berries aligned with the verbal statement “bring home a fresh fruit orchard” generated “positive inferences” from viewers (Phillips and McQuarrie, 2005). In other research, happy or angry faces were flashed on a screen while people examined Chinese ideographs. The type of face affected “liking ratings” of the ideographs. Even small alterations in an image can impact product evaluations. For instance, changing the camera angle of a product can influence the viewer’s attitude toward the product (Meyers-Levy and Peracchio, 1992).

Online, the visual design of an e-commerce website is important because it improves website aesthetics and emotional appeal (Garrett, 2003; Liu et al., 2001; Park et al., 2005), which may in turn lead to more positive attitudes toward an online store (Fiore et al., 2005).Loiacono et al. (2007) created an instrument to measure consumer evaluation of websites, and found that visual appeal and consistent images resulted in entertainment for the user, ultimately leading to intentions to reuse the site in the future. In research on banner ads, different formats using either text or images were manipulated. Viewers consistently rated the versions with images as more positive and effective (Yoon, 2002).

Age makes a difference as to how images are processed and appreciated. For example, some studies suggest that web aesthetics and visual design may be especially important to Generation Y users (e.g. born 1977 to 1990) (Tractinsky, 2004; 2006). Other studies have shown that visual appeal of the homepage for an online vendor impacts impressions of vendor image and merchandise quality for Generation Y users (Oh et al., 2008). Users younger than age 25 seek fun when shopping online, and respond positively to personalized product offers, custom-designing products, and seeing the profiles of previous customers who purchased an item. In a two pronged study that included surveys and investigations where participants looked at a web page using an eye-tracking device, Generation Y users exhibited specific preferences for a large main page, images of celebrities, little text, and a search feature (Djamasbi et al., 2010). In research that compared Generation Y users and Baby Boomers (e.g. born 1946 to 1964) using an eye-tracking device and self-report measures, both generations reported similar aesthetic preferences, and liked pages with images and little text (Djamaski et al., 2011). However, viewing patterns differed, with Baby Boomers having significantly more eye fixations that covered more of the pages.

38.3.4 Human Images and Image Appeal

Online, images of people are used to induce favorable emotional responses (Riegelsberger et al., 2003) and to draw attention (Tullis et al., 2009). Adding images of players engaged in an online text chatting game increased cooperation (Zheng et al., 2002). The use of human images is thought to increase the website’s aesthetics and playfulness—and therefore positively influence the user (Liu et al., 2001).

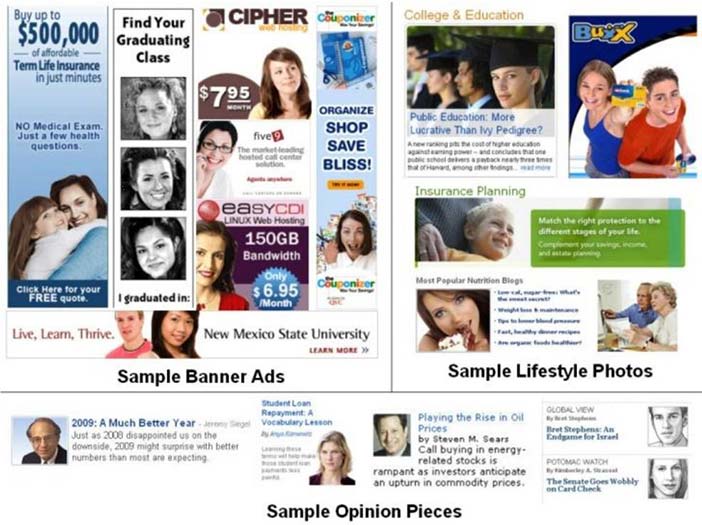

For many years advertising has relied on imagery using “friendly faces” to build a positive attitude toward products (Giddens, 1990), as shown with the use of faces on sample banner ads, lifestyle photos, and opinion articles in Figure 15.

Author/Copyright holder: Courtesy of Various Copyright Holders (synthesized by Tullis et al., 2009). Copyright terms and licence: compositeWorkWithMultipleCopyrightTerms (Work that is derived from or composed of multiple works with varying copyright terms and/or copyright holders).

Figure 38.15: Sample Use of Faces (in Tullis et al., 2009)

Online trust can be established through virtual re-embedding of content and social cues (Riegelsberger et al., 2003; 2005). In a study using pages from the online shop of a well-known British supermarket chain, identical pages were created with one exception: one page contained a photograph of a human face while another had a box of text the identical size as the photograph. Viewers were more attracted to the photograph, leading to the conclusion that “the face is a very important source of socio-emotional cues....Advertisers have found that photographs of faces attract attention and create an immediate affective response that is less open to critical reflection than text we read” (Riegelsberger, 2002, p. 1). For an online banking website, inclusion of employee photographs resulted in attributions of trustworthiness (Steinbrück et al., 2002). A photograph of the author in an online magazine article resulted in greater perceived trustworthiness of the article (Fogg et al., 2001).

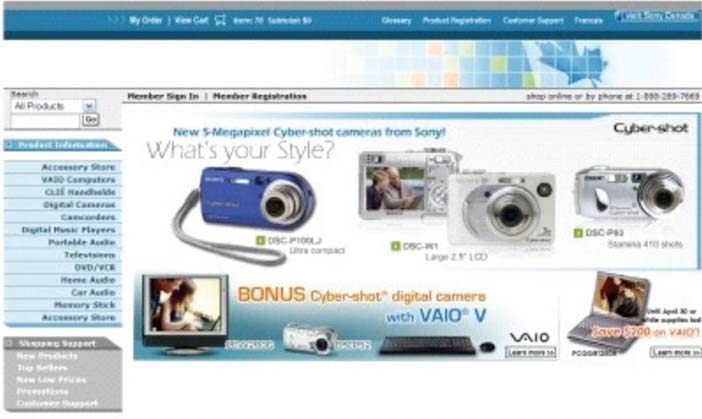

Using an eye-tracking device, Djamasbi et al. (2012) examined the impact of facial images on viewing behavior, and the number of user eye fixations on web pages (footnote 17). Using the theory of visual hierarchy (e.g. the order in which information is communicated to users) objects on the website were manipulated related to the presence or absence of facial images, and their location either above or below the mid-point on the page. Typically, users follow an F-shaped pattern when viewing web pages—that is, they look along the left hand portion of the page, and particularly the top left hand area (Buscher at el., 2009). Figure 16 shows the pages used in Djamasbi’s study.

Author/Copyright holder: Courtesy of Unknown Website (manipulated in Djamasbi et al., 2012). Copyright terms and licence: pd (Public Domain (information that is common property and contains no original authorship)).

Figure 38.16: Web Pages with Faces and their Location (in Djamasbi et al., 2012)

Findings from the above study (Djamasbi et al., 2012) revealed that faces did not necessarily increase viewing time or the number of people who viewed the areas with images. However fixation patterns in these areas were affected. For instance, viewing was more dispersed when faces are present - and thus users scanned faces, titles, and text (Figure 17, a and b. Also, faces above the mid-point on the page attracted significantly longer fixations, which negatively affected user performance on a performance task since users diverted their attention from key information such as titles.

Author/Copyright holder: Unknown Website (manipulated in Djamasbi et al., 2012). Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine (as permission could not be obtained). See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "allRightsReserved-UsedWithoutPermission") on the page copyright notice.

Figure 38.17: Heat Maps when Browsing Faces or Text (in Djamasbi et al., 2012)

38.3.5 Images and Culture

Cultural differences exist with respect to the use of images. In collectivist cultures such as China or Japan, users have a strong preference for visuals (Szymanski and Hise, 2000) including pictures, bright colors, and animation (Cyr et al., 2005). Design elements including Visual Design influence user trust, which also varies by country. In an e-commerce investigation in Canada, Germany, and China, Visual Design only resulted in trust for Chinese users (Cyr, 2008). In a study of Indian websites, images were found to be important carriers of culture, and most websites have pictures of Indian people and culture (Kulkarni at el., 2012). However, as the researchers note (Ibid), globalization is changing the type of imagery used to be reflective of Western culture (Figure 18).

Author/Copyright holder: Westside. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine (as permission could not be obtained). See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "allRightsReserved-UsedWithoutPermission") on the page copyright notice.

Figure 38.18: Westernization of an Indian Website (Kulkarni et al., 2012)

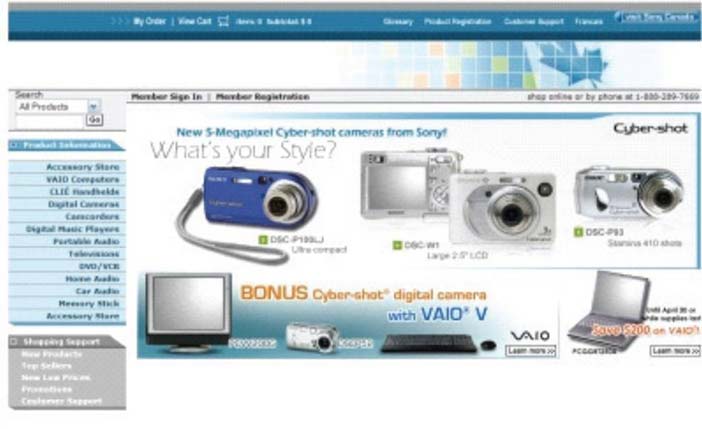

Other research examined the relationship of human images to image appeal, perceived social presence (e.g. the warmth and sociability of the website), and trust (Cyr et al., 2009). A controlled experiment was conducted with different levels of human images represented on a web page: human images with facial features, human images without facial features, and no human images (Figure 19).

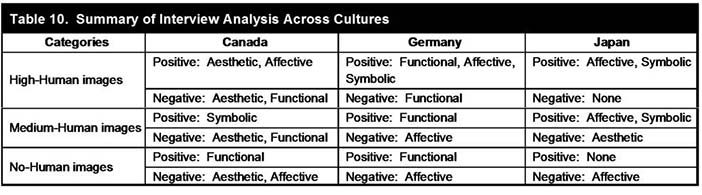

Data was collected on websites for Canada, Germany, and Japan using a questionnaire, interviews, and an eye-tracking device (Cyr at al., 2009). The model was supported in that human images with facial features resulted in user perceptions that the website was more appealing, had warmth or social presence, and was more trustworthy. Of interest, participants in all countries spent the most time viewing the partial image (e.g. the condition with human images but with no facial features) which they described as “unnatural” and “distracting”. Additional analyses revealed subtle differences in the perception of human images across the three countries. While the general impact of human images appears universal across country groups, based on interview data four concepts emerged: aesthetics (visual qualities such as pretty or bright); symbolism (implied meaning — for instance an image of a man and little girl may be a representation of father and daughter); affective property (and eliciting emotion); and functional property (structural properties such as information design, navigation, layout). Based on interview data, participants from each culture focused on different concepts based on both positive and negative assessments (Figure 20).

Author/Copyright holder: Sony Electronics Inc. (manipulated in Cyr et al., 2009). Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine (as permission could not be obtained). See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "allRightsReserved-UsedWithoutPermission") on the page copyright notice.

Author/Copyright holder: Sony Electronics Inc. (manipulated in Cyr et al., 2009). Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine (as permission could not be obtained). See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "allRightsReserved-UsedWithoutPermission") on the page copyright notice.

Author/Copyright holder: Sony Electronics Inc. (manipulated in Cyr et al., 2009). Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine (as permission could not be obtained). See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "allRightsReserved-UsedWithoutPermission") on the page copyright notice.

Figure 38.19 A-B-C: Three Levels of Human Images on a Canadian Website (in Cyr et al., 2009) (Top - No Human Images, Middle — Human Images but No Facial Features, Bottom — Facial Images

Author/Copyright holder: Cyr et al., 2009. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Figure 38.20: Summary of Emerging Concepts by Culture (in Cyr et al., 2009)

It is also interesting to reflect on the interview comments from participants in this study, and how the various images impacted them (Cyr at al., 2009). Overall, users in all countries liked the human images with facial features. It was noted: “Pictures of people add a human level and we can relate to them” (Canada); “It’s important to show images with people, their smiles, their emotions” (Germany); “The sites with the images of people looked warm and trustworthy” (Japan). In contrast, reactions to the no-human image condition are largely negative. Participants across the three countries criticized the blank images, and perceived the website as unfriendly. According to one Canadian: “When the site just had the actual product and absolutely no human images, it did make it look stark.” Alternately, a few Canadians and Germans perceive websites with no human pictures as functional. That is, the site is not cluttered with distracting pictures (Cyr at al., 2009).

Between countries, Canadians tended to focus on aesthetic aspects of the images and website, while Germans and Japanese did not mention them. Germans commented on symbolism (i.e., community activities) of the images, as well as functional properties of the website. In the latter case, one German remarked, “I don’t like pictures of people on the site. If I want to buy a computer, I don’t need anything with human pictures on it. I just want to know the facts.” Japanese participants mentioned they also like the community related symbolism of these images (Cyr at al., 2009).

38.3.6 Summary

The preceding evidence shines a light on the importance of color and image for eliciting user emotion on websites. While research, particularly usability studies, has proven this for some time, in the current context empirical linkages are established between color and images with specific user outcomes such as trust, satisfaction, and loyalty, among other reactions. Although research has generally considered the impact of design principles such as color or images, it is significant that considerably less attention has been paid to website design elements and their variance across cultures. This is the case, despite the importance of cultural sensitivity of website design. Thus, it would be beneficial if both researchers and practitioners were to investigate website localization and the impact it has on perceptions and emotions in diverse cultures. Other characteristics, such as age or gender likewise deserve attention concerning the use of color and imagery.

Finally, while most research relies on survey data to evaluate website design characteristics, studies which utilize multiple sources of data collection yield rich and interesting results. For instance, in some of the research discussed above, interview data and eye-tracking results provide nuanced information as to how users react to design elements. In addition to unconscious data provided by an eye-tracker, in recent studies physiological measures such using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) have been used to explore topics in the information systems domain. As one example, in a study measuring user brain activity while shopping on eBay using fMRI, differences were found between men and women concerning brain areas that encode trustworthiness (Riedl et al., 2010). (footnote 18)

38.4 Social Elements and Website Design

Building on the preceding, but broader than human imagery, there are a variety of socially oriented website elements which can elicit hedonic responses in users. Website social elements, and more specifically website social presence as mentioned above, is known to result in user enjoyment (Cyr et al., 2007; Hassanein and Head, 2007). In the following, perceived social presence is discussed, including differences between men and women regarding desired levels of social presence. In addition, cultural implications for social design elements are outlined, although little research has been conducted in this area.

38.4.1 Perceived Social Presence

Perceived social presence has been defined as “the extent to which a medium allows users to experience others as being psychologically present” (Gefen and Straub, 2003, p. 11). Perceived social presence implies a psychological connection with the user who perceives the website as “warm”, personal, sociable, thus creating a feeling of human contact (Yoo and Alavi, 2001). (footnote 19)In one study, social presence has been segmented into “affective social presence” and “cognitive social presence” (Shen and Khalifa, 2009), although most research uses a uni-dimensional construct. Affective social presence refers to emotional responses aroused in the user by virtual social interaction. Cognitive social presence refers to the user’s belief regarding relationships with others in the social context.

Examples of website features that encourage social presence are socially-rich text content, personalized greetings (Gefen and Straub, 2003), human audio (Lombard and Ditton, 1997), or human video (Kumar and Benbasat, 2002). Gefen and Straub (2003) suggested that pictures and text are able to convey personal presence in the same manner as do personal photographs or letters. In addition to perceived social presence resulting in online enjoyment, social presence has implications for website involvement (Kumar and Benbasat, 2002; Witmer et al., 2005); website trust (Cyr et al., 2007; Gefen and Straub, 2003; Hassanein and Head, 2007); and utilitarian outcomes such as perceived usefulness (Hassanein and Head 2005-6; 2007).

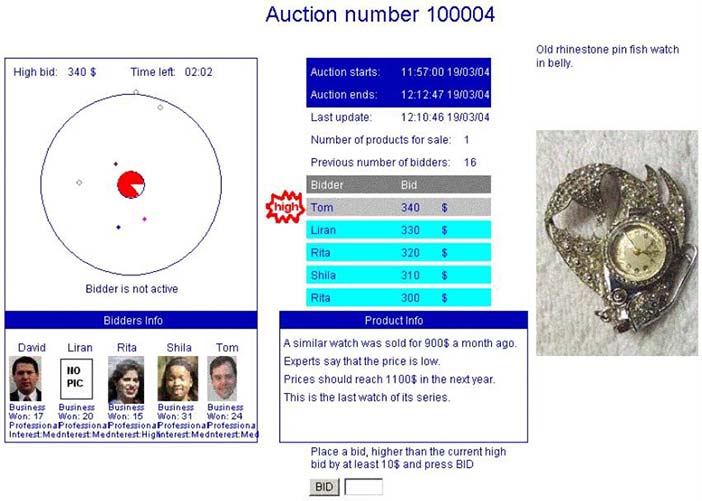

In research on Internet auctions, two conditions of social influence were presented to participants: (1) interpersonal information in the form of text, or (2) “virtual presence” that included pictures of other bidder’s faces (Rafaeli and Noy, 2005) (Figure 21).

Author/Copyright holder: Rafaeli and Noy, 2005. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Author/Copyright holder: Rafaeli and Noy, 2005. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine (as permission could not be obtained). See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "allRightsReserved-UsedWithoutPermission") on the pagecopyright notice.

Figure 38.21 A-B: Difference Levels of Social Influence on Websites (in Rafaeli and Noy, 2005)

Results indicated the effect of interpersonal information on bidding behavior was not as important as the effect of virtual presence. The authors explained their results as being related to “the enthusiasm with facial cues [by users] and perception of other’s presence” (Rafaeli and Noy, 2005, p. 172). The incorporation of human or human-like faces in online environments provides online participants with a stronger sense of community (Donath, 2001).

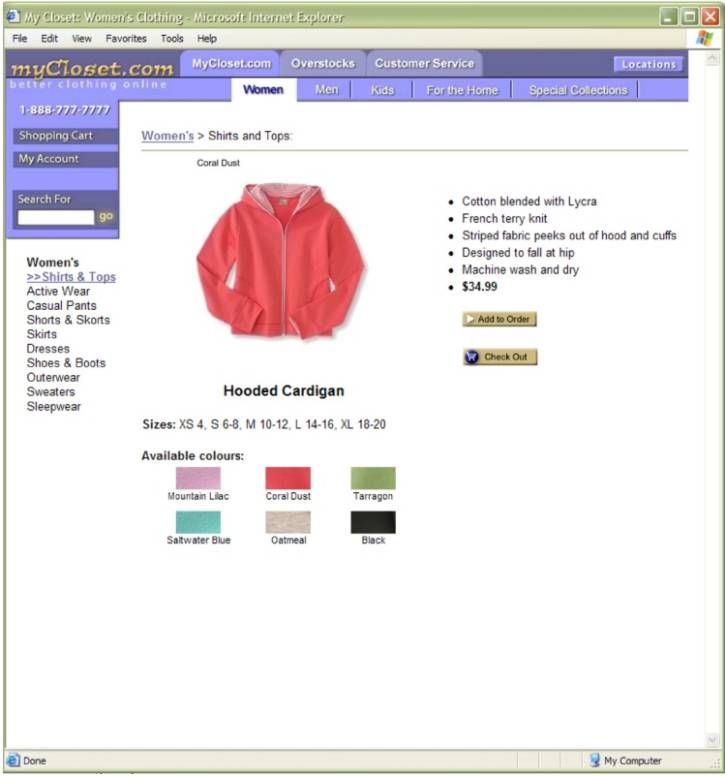

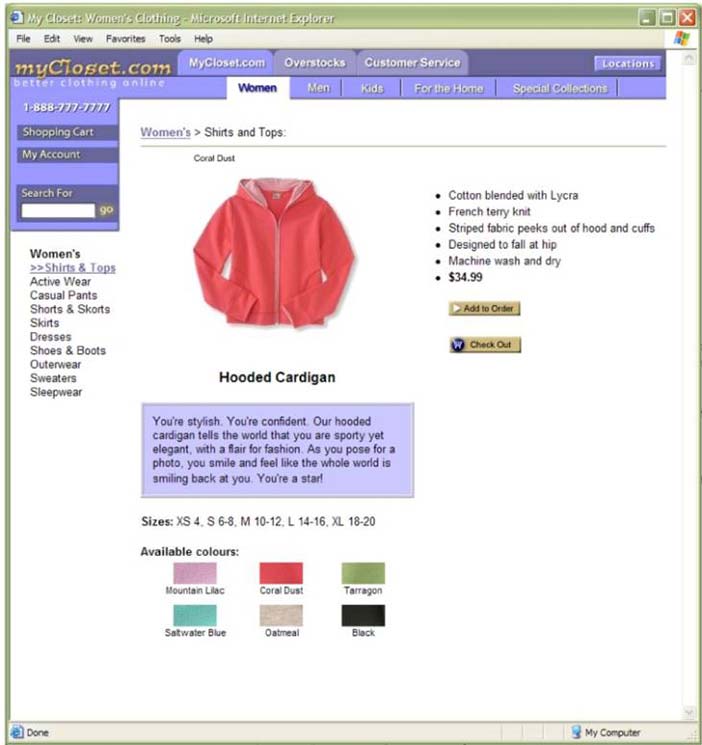

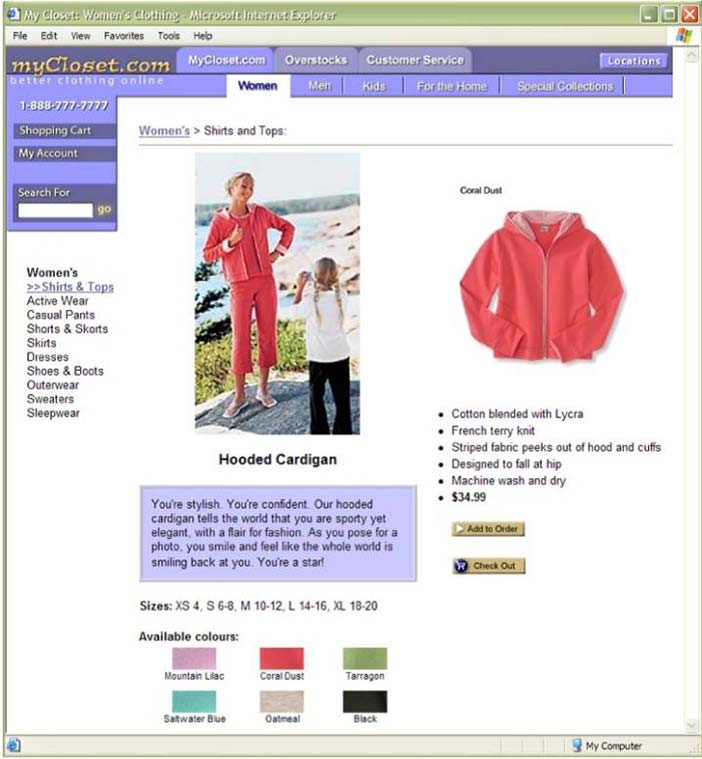

Previous research has manipulated Internet shopping conditions to investigate online social presence on an apparel website (Hassanein and Head, 2007). In a low social presence condition functional text and a basic product picture appeared; in the medium condition a basic product picture appeared with emotive/descriptive text; and in the high social presence condition pictures depicted human figures interacting with the product as well as rich and emotive text (Figure 22).

Author/Copyright holder: MyCloset.com. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine (as permission could not be obtained). See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "allRightsReserved-UsedWithoutPermission") on the page copyright notice.

Author/Copyright holder: MyCloset.com. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine (as permission could not be obtained). See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "allRightsReserved-UsedWithoutPermission") on the page copyright notice.

Author/Copyright holder: MyCloset.com. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine (as permission could not be obtained). See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "allRightsReserved-UsedWithoutPermission") on the page copyright notice.

Figure 38.22 A-B-C: Difference Levels of Social Presence on Websites (in Hassanein and Head, 2007)

Hassanein and Head (2007) concluded that for shopping websites featuring apparel, higher levels of social presence, created in part through human figures, positively impacted perceived usefulness, trust, and enjoyment. Further, as the degree of perceived social presence increases, there is an increased impact on emotions and behavior (Argo et al., 2005). Alternately, the type of website determines whether or not the development of social presence is necessary. For instance, Hassanein and Head (2005-6) conducted another study in which an apparel website was compared to a website selling headphones. For the website selling headphones higher levels of social presence did not positively impact user attitudes, since the user was primarily seeking detailed product information.

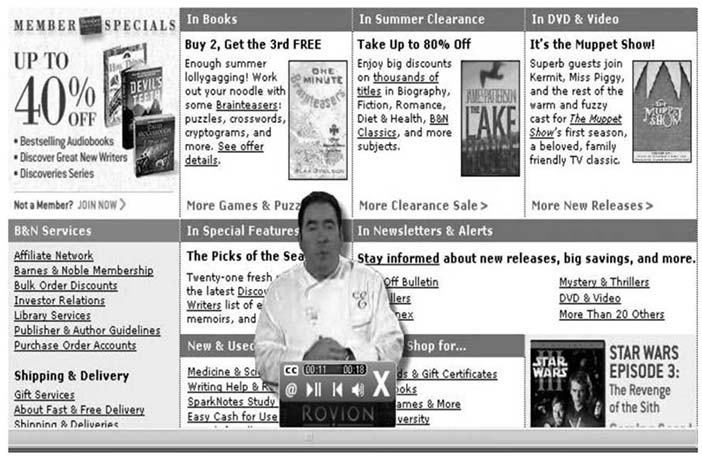

38.4.2 Additional Forms of Online Social Influence

In related research, perceived “website socialness” was tested for relationships to perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, enjoyment, and ultimately intention to use the website (Wakefield et al., 2011). To create greater variability in the experiment two types of websites were used: window blinds (utilitarian) and entertainers (hedonic). Participants were exposed to the website with either an interactive streaming video guide or the identical website but without the guide. The guide (Figure 23) featured four aspects of social cues: social role (the guide), human voice, language, and interactivity. The videotaped human guide that appeared on the screen invited users to interact with the guide, and was meant to make the pages “come alive”. Results of this study supported all hypothesized relationships. Although contrary to the findings of Hassanein and Head (2005-6) there were no differences in how the model operated between the utilitarian and hedonic website conditions.

Author/Copyright holder: Barnes and Noble, and Rovion. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine (as permission could not be obtained). See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "allRightsReserved-UsedWithoutPermission") on the page copyright notice.

Figure 38.23: An Interactive Shopping Guide (in Wakefield et al., 2011)

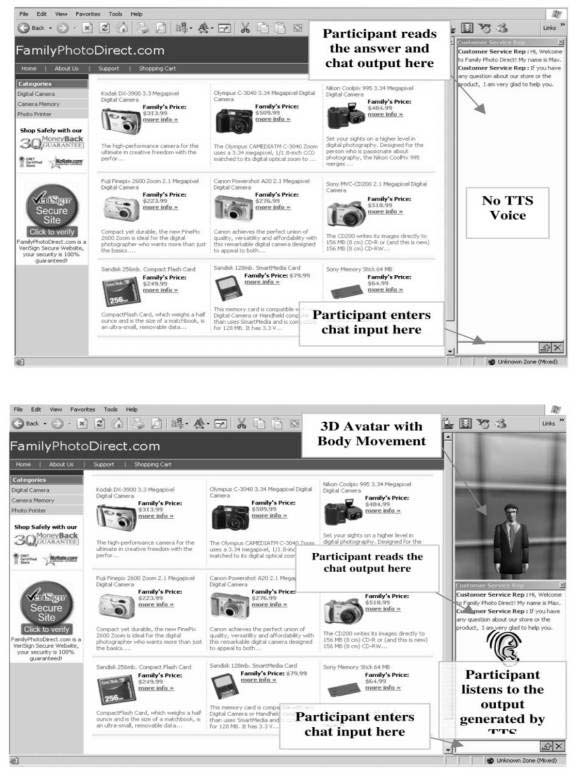

Further, online shopping assistants are interactive technological artifacts that provide information and respond to online consumers. As “social actors” on the electronic stage, online shopping assistants potentially build a relationship with the user that results in enjoyment, trust, perceived usefulness, and ultimately in reuse intentions (Al-natour et al., 2005). If the personal shopping assistant is perceived by the user to be similar both in personality and behaviors, then it was more positively evaluated by the users. Additional studies by Benbasat and his colleagues examined “live help” functions through instant messaging or text chatting to facilitate interactions between users and online customer service representatives (Qui and Benbasat, 2005). Rather than text-based communication, users were exposed to socially rich environments which included computer-generated voice and humanoid avatars. These researchers found that text-to-speech voice delivered aloud through a 3-dimensional avatar significantly increased cognitive and emotional trust toward the customer service representative. Although these findings are several years old, the use of rich and personalized service agents still only appears selectively on websites. Figure 24 illustrates treatment websites featuring web pages with and without the Live Help interface.

Author/Copyright holder: FamilyPhotoDirect.com. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine (as permission could not be obtained). See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "allRightsReserved-UsedWithoutPermission") on the page copyright notice.

Figure 38.24: A Live Help Interface with both Voice and Avatar (in Qui and Benbasat, 2005)

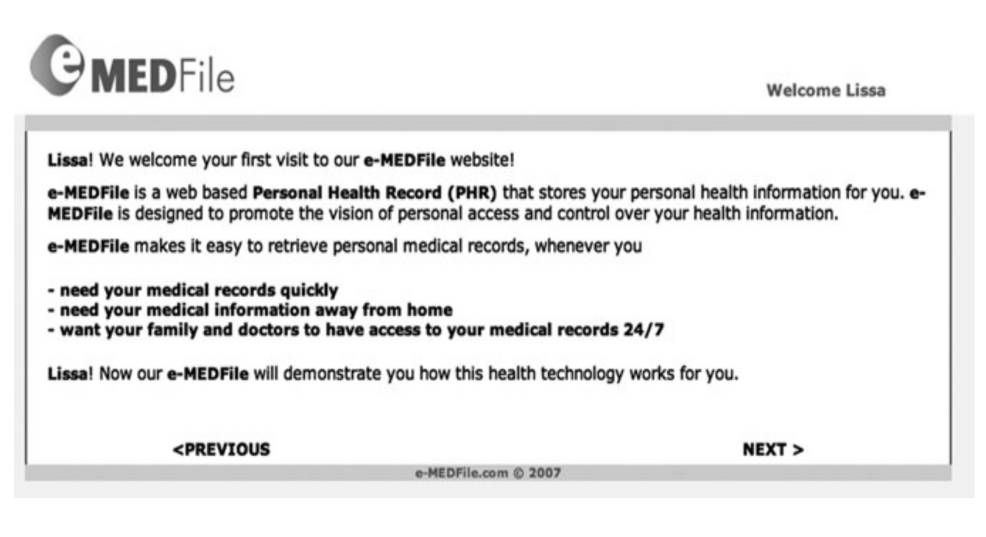

E-health is an emerging and important area for the application of social elements for website design. In a study of disclosure and personal health records, Lee and LaRose (2011) studied the impact of personalized social cues for two types of information disclosure (e.g. embarrassing information and descriptive information). Information disclosure was further tested related to user outcomes as positive (e.g. social trust and customization of their requests) or negative (embarrassment and information abuse). To manipulate the level of personalized social cues, in the high immediacy condition users were personally greeted using their first name (e.g. “Welcome Lissa”) (Figure 25). In addition, the high immediacy website featured an interactive review session during which the user is praised and encouraged (e.g. “Excellent, Lissa! That is the right answer! Or “Try again, Lissa. You can do it!” Ibid. p. 339). Alternately, the low immediacy website did not host these social cues. An interesting finding from this study is that regardless of the type of information (embarrassing or descriptive), exposure to a high immediacy website with personalized social cues increased the level of information disclosure, signaling this as an important element of design in an e-health context.

Author/Copyright holder: eMedFile. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine (as permission could not be obtained). See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "allRightsReserved-UsedWithoutPermission") on the page copyright notice.

Figure 38.25: Screenshot for an Online Medical Website (in Lee and LaRose, 2011)

38.4.3 Men, Women and Social Cues

In 2013, “across all ages women interact more online than men”. (footnote 20)Overall, men tend to have more positive evaluations of websites than women (Rodgers and Harris, 2003), including favorable attitudes toward online advertising (Parsa et al., 2011). In 2004, women were found to be less satisfied with websites, and trust them less than men (Garbarino and Strahilevitz, 2004), an outcome that remains current today.

Generally, women have lower perceptions of websites than men regarding information richness, communication effectiveness, and the communication interface (Cyr and Bonanni, 2005). Women also have more negative evaluations of the presentation of product information and site organization, and are significantly less satisfied with navigation formats than men (Cyr and Bonanni, 2005). Visualization characteristics such as preferences for color, shapes, and use of expert language vary between males and females (Ozdemir and Kilic, 2011). Further, differences between men and women were found for use of voice, color and language (Mahzari and Ahmadzadeh, 2013).

Men tend to focus on utilitarian aspects of shopping websites. Accurate product descriptions and fair pricing are very important for men (Chen and Hu, 2012;Ulbrich et al., 2011). Men like websites that allowed them to custom design products (Burke, 2002). Alternately, women dislike copious amounts of interactivity on the site, and find animations less meaningful than men. Women prefer websites with less clutter and fewer graphics. Women shoppers indicate they “must have” online product prices, a list of sale items, and personalized product discounts. More than men, women are receptive to electronic shopping lists, and having the website save a list of past purchases. Female web shoppers consider return labels (i.e. ability to return an item) more important than men (Ulbrich et al., 2011).

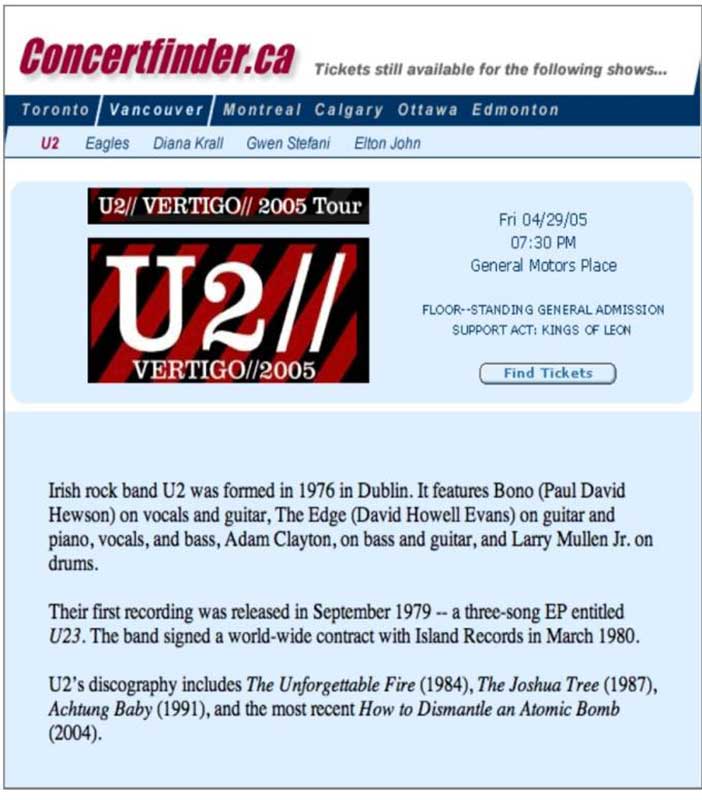

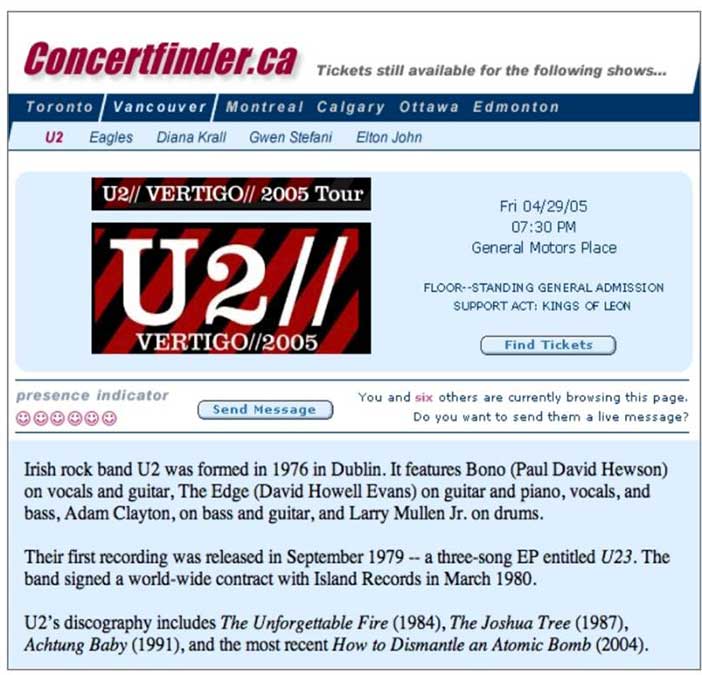

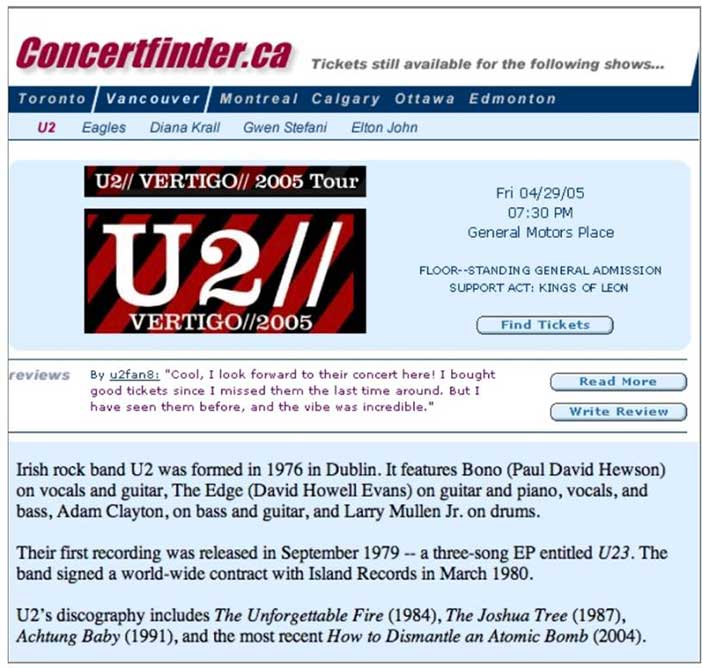

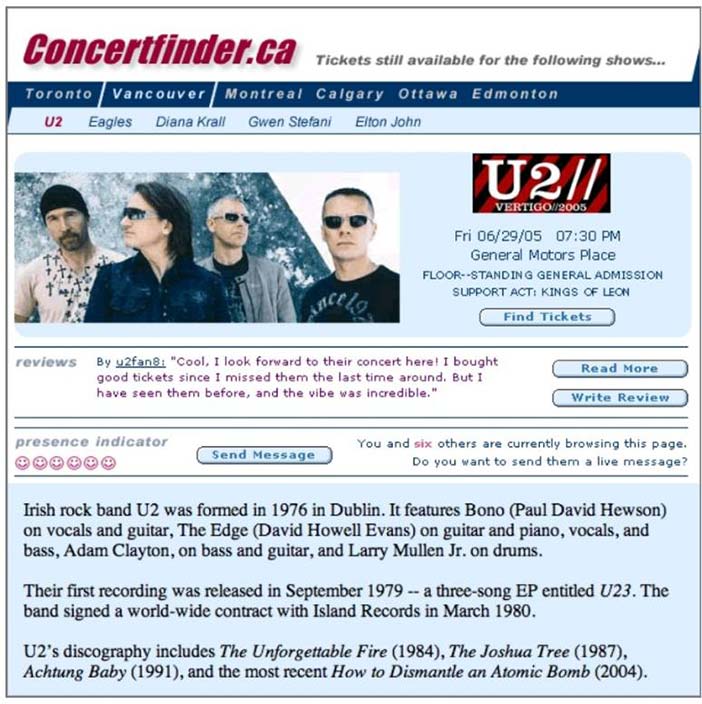

Concerning different social needs between men and women, the impact of social elements on websites is expected to be perceived differently between the sexes. To test this assumption, in one study five different levels of social presence were created for comparison between men and women (Cyr et al., 2007). All conditions featured the same content (for the same five performers or bands), but differed only in terms of social presence elements. Condition 1 was the basic treatment that included text and the band logo. In Condition 2, a photo of the band was included. Conditions 3 and 4 featured different interactive elements that allowed for discussions and reviews/ratings. Specifically, Condition 3 offered users the opportunity to open up a blank window and send a live chat message to other users assumed to be concurrently browsing the web page. The number of users browsing the current page was represented by a "presence indicator" consisting of a static image of several ‘smiley face’ icons. Condition 4 offered users the opportunity to see reviews from other users and write their own review for the performer/band. While Condition 3 was meant to simulate synchronous interaction, Condition 4 simulated asynchronous interaction with other website users. Finally, Condition 5 included all of the above mentioned features (text, logo, photo, synchronous chat, asynchronous reviews). (Figure 26(a-e)).

Author/Copyright holder: Dianne Cyr. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Condition 1 (Basic)

Author/Copyright holder: Dianne Cyr. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Condition 2 (Photo)

Author/Copyright holder: Dianne Cyr. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Condition 3 (Synchronous chat)

Author/Copyright holder: Dianne Cyr. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Condition 4 (Asynchronous reviews)

Author/Copyright holder: Dianne Cyr. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Condition 5 (All)

Figure 38.26: Difference Levels of Social Presence on Websites (in Cyr et al., 2007)

Results from this research indicated women sought hedonic content to “engage” them, whereas men focused more on information they felt was missing (Cyr et al., 2007). For a website with minimal social presence, women commented it was "boring, not enough pictures, no sense of vibrancy", that it had "no emotion, it does not evoke any response...a cold non-interactive site", that "visually, it is not very appealing at all. . . there should be more pictures", and that it was "not friendly". In contrast, when commenting on the higher social presence conditions, females noted they "felt relaxed and enjoyed reading it", "it aroused [their] curiosity of each band, making [them] want to listen to all of their music", and it felt "more like a party chat room than a cold, impersonal website just selling stuff/tickets" (ibid). In this study, perceived social presence was significantly related to perceived usefulness, trust, and ultimately loyalty for both men and women, although only for women did it result in a significant relationship of enjoyment to loyalty (ibid.).

Whether a man or a woman designs the website impacts user perceptions, although in 2013 only 5% to 20% of software developers are women (footnote 21). Men have a preference for website pages produced by men, while women prefer web pages produced by women. For 30 male-produced and 30 female-produced websites, significant differences were found between the two sets of websites on 13 of 23 factors with respect to navigation and visual content. Websites designed by women had links to a larger number of topics than those designed by men. Language was used differently, with more references to competitiveness on male-produced websites. Of five language elements examined, there were significant differences on four of these elements with women more likely to use abbreviations and informal language. In particular, visual design varied between websites aimed at men versus women, with images of one’s own gender appearing on the website. Women were more likely than males to use rounded rather than straight shapes, more colors, a horizontal layout, and informal images (Moss et al., 2006).

38.4.4 Social Elements of Website Design and Culture

Only a few studies have been conducted in which hedonic website design features are systematically modeled across diverse cultures, although recently research in this area is beginning to emerge.Hassanein et al. (2009) aimed to determine if perceived social presence is culture specific or universal in online shopping settings. These researchers found that for Chinese and Canadian users, social presence led to perceptions of usefulness and enjoyment, but for Canadians social presence resulted in trust only.

As discussed earlier, Cyr and her colleagues conducted two separate research investigations with Canadian, German, and Japanese users regarding their reaction to visual design website elements. In the first study, survey data indicated that human images universally result in image appeal and perceived social presence; while interviews and eye-tracking data suggested participants from different cultures experience design images differently (Cyr et al., 2009). In the second study, website color appeal was found to be a significant determinant of website trust and satisfaction, with differences across cultures (Cyr et al., 2010.

38.4.5 Summary

Creating websites that are warm and inviting is clearly important to attract users and to encourage them to return or to purchase in the future. Despite this, many websites are lacking in this critical element. Social elements seem to be of particular importance to women, although they are also important to men. It is expected that if women dislike the online tone and format, then they will likely be less emotionally involved in the website or shopping experience. Therefore, there is merit in focusing on designing for a female audience in order to increase enjoyment, involvement, trust, and satisfaction for this group. One way to facilitate this process is to utilize more women in the design process. In addition to considering social elements of website design in domestic markets, there is room for further research and exploration of this topic in international contexts as well. As such, this presents a fruitful area for future studies.

38.5 Future Directions

While generally under-researched, the use of emotion in website design is gaining prominence and thus deserves further investigation. Identifying and systematically clarifying website design elements that result in positive emotional responses in the user has not only theoretical merit, but practical purpose as well. Taking a cue from the research in this paper, a number of avenues for future investigation or consideration are suggested:

Definition and Model Development of Emotion in Websites — As noted early on, there are numerous definitions which all are related to emotion on websites. It is not entirely clear which website design elements result in which user emotions, although research in this area is evolving. Some researchers are proposing the development of integrated models for understanding affective responses (e.g. Lowry et al., 2013; Zhang, 2013) and work in this area will likely continue with useful outcomes for both academics and those responsible for the design of effective websites.

Instrument Validation — Although there are numerous scales of usually four or five items that measure types of affective or emotional responses, there are few comprehensive instruments that serve this purpose. Hence, there is value in systematically developing and validating such an instrument.

Methodological Diversity — Although research on website design and information design has typically relied on surveys with single or multiple item scales, more recently researchers have been diversifying their techniques to obtain different types of data. This might include research into emotion and website design that also includes neurophysiological techniques such as fMRI, an eye-tracking device to determine exactly where and how users respond to emotional content on web pages, or a combination of these methodologies.